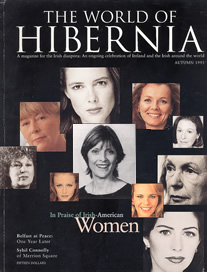

WORLD OF HIBERNIA

Autumn 1995

A magazine for the Irish Diaspora: An ongoing celebration of Ireland and the Irish around the world.

In Praise of Irish-American Women

Kildare-born Michele Burke was only just in the door from Dublin. She had arrived back in Los Angeles after three months in Ireland. The two-time Oscar-winning makeup artist had recently wrapped up filming on a new production of Moll Flanders, Daniel Daffoe’s wicked restoration comedy, with Morgan Freeman, Stockard Channing, Brenda Fricker, and John Lynch.

“Dublin was the perfect setting for the film. Its Georgian character was made to order for the setting of 18th-century London,” she observed. Burke is at home in California. She is at home in films.

Her first Academy award came for her brilliant work on the prehistoric epic Quest for Fire. Her most recent was for Neil Jordan’s imaginative production of Anne Rice’s Interview with the Vampire. In the world of Hollywood, Burke’s name has genuine success to it.

Dublin was in great form for Molt Flanders. “The city is thriving, booming,” Burke noted with a surprise ring in her voice. “When you go back to Ireland and see it, you realize that it is having an extra-ordinary boom. In the shops you have to fight to get to the cashier. Dublin is actually crowded,” she admitted, “Bewley’s was too crowded to go into.” Our conversation quickly became an instant run across Dublin streets. Such excitement is not unusual.

Dublin’s lamentable public face of the 1970s is long gone. It is polished now, fresh-scrubbed. Dublin’s character has exponentially widened. Particularly in relation to the arts. Burke’s career provides her with an unusual vantage point from which to measure the success of Dublin’s film industry.

“The arts are so big,” Burke quickly added. “Anyone working in the area of the arts or film really excels. I do make-up,” she said with self-effacing quiet. “I head up the department, I design the look. I create the characters. Dublin has been ideal. The old part retains that 1700s look. We filmed in really neat little places. We just wormed our way around this archway, that exte- rior. Film is thriving in Dublin.”

Irish films have offered wide tax incentives to foreign film directors and producers. The cooperative, jovial characters who have their fingers in Irish film are producing great tales. Much of it relishes the extraordinary ability of the Irish to tell a story. Such ability is a national treasure.

“My husband was amazed at the way people describe things. There is a dramatic capacity for creating larger meaning. He’d be listening to people and their proud facility for exaggeration and nuance. He’d turn to me and say, `What are they saying?’ But, you know, here in the U.S. people don’t talk. Not the way the Irish do. My brother was walking down a street in Dublin and a pigeon messed on him. He looked up and said, `Well, thank God cows can’t fly.’ That’s brilliant. It’s imaginative. It was spontaneous.”

Since arriving in California nine years ago from Montreal, where she settled after leaving Ireland, Burke has acclimatized herself to California living. “There are plenty of Irish in California. There’s plenty of everybody. It’s a very cosmopolitan place, people have come from all over. Our friends are German, French, and British. Out here it is normal to be from somewhere else.”

An impressive imagination has brought deserved success for Burke. Her two Oscars hardly enter the conversation. She does not wear them on her coat. Her industry reputation is magic, her fiery, Celtic vision solid gold.

Attachments

- hibernia (27 kB)